The Relationship of Foot Posture to Pelvic Position

Monday, July 12, 2010 at 8:27AM

Monday, July 12, 2010 at 8:27AM Stuart Currie, DC

Director of Research, Sole Supports.

INTRODUCTION

It seems obvious that the foot’s alignment or posture can have an effect on the kinetic chain and influence proximal structures, from the tibia to the femur to the pelvis and low back. What exactly do we know about this relationship, and what are the clinical findings to look for when evaluating patients?

A previous article discussed the relationship of back pain to foot alignment and what evidence exists for the treatment of back pain with foot orthotics; this discussion will focus on what the literature can tell us about specific alignment changes in the pelvis that can occur due to altered foot position. The pelvis is situated in the center of the body, and connects the movement of the lower limbs to the segmental motion of the spine. It is a functional link, through which loads are transferred in a proximal and distal manner. Although suggested often, until recently, its position and movement as related to foot posture was mostly hypothesized.

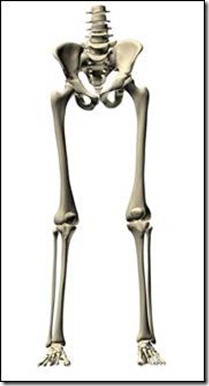

We now know that both bilateral and unilateral calcaneal eversion (part of pronation) can cause pelvic anteversion in the standing position1. Recommendations from this study included that excessive pronation be considered when evaluating pelvic misalignment. Another study has shown that pelvic alignment is influenced by foot alignment with an anterior tilt of the pelvis being induced by wedging the feet into pronation2. Using motion analysis this study also illustrated the link between foot and pelvis, showing that changes in calcaneal alignment (pronation) produce resultant shank and thigh internal rotations.

When considering any study using measurements of static pelvic position it is important to remember that the results (unless otherwise accounted for in the study design) are a reflection of the immediate effects, and not a prolonged adaptive effect. As we know, every human body is unique and can adapt in different ways to the same perturbation. In addition to temporal considerations, the distinction between static measurements and dynamic function is an important one, for it is easy to forget that the static evaluation is a snapshot at one point in time. How is the snapshot related to the gait cycle and at what point is the observation made? A caveat to pelvic evaluation is that research in foot and gait analysis reveals the lack of correlation between static measurements and dynamic function3; therefore, it would be unwise to assume postural measures of the spine and pelvis in the standing position present superior insight. In other words, static alignment is suggestive but does not reveal how the pelvis, hip, knee, ankle, and foot respond to ground reaction force and body weight4.

Figure 1. – Asymmetrical pronation of the right foot can result in internal rotation of the tibia, internal rotation of the femur, and anteversion of the pelvis.

If we know that an anterior pelvic tilt can be caused by pronation the logical question is, can it be reversed? This has been demonstrated in a study that showed increasing the arch height (through the use of low-dye taping) resulted in effects that were seen throughout the kinetic chain. In addition to changes in lower limb muscle activity and motion, an increase in total excursion of the pelvis was seen due to a more posterior tilted pelvic position5. Interestingly, even after removal of the tape and a subsequent lowering of the arch, the pelvis maintained a more posterior tilted position during 10 minutes of walking. It is this type of finding with sustained effects even after the intervention is removed, that leads to a discussion of how the neuromuscular system controls the way we move and learns to maintain a preferred posture.

The anterior pelvis is important to the chiropractic evaluation for well agreed upon reasons. In addition to other problems, the anterior pelvis with its resultant superior to inferior movement of the symphysis pubis, can result in secondary dysfunction from imbalances of the adductors and lower abdominals6. A comprehensive evaluation of pelvic and foot posture may include the following observations. With the patient standing, a side-to-side visual comparison of the patient’s feet (bunions, hammer toes etc.) provides clues as to differential function. Observe genu valgus, genu varus, the rearfoot angle, arch height, and hallux dorsiflexion. Heel walk and toe walk illustrate the function of the dorsiflexors and plantarflexors. With the patient seated and their legs hanging, tibial torsion and varum can be evaluated. In the supine position, foot segmental motion, forefoot flexibility, ankle plantar flexion and dorsiflexion can be evaluated. Hip and knee flexion provide information about the shock absorbing capability of the patient. Limitations in hip extension and internal/external rotation can be observed prone, which all provide information as to the cause of pelvic dysfunction. While an exhaustive discussion of the various normal ranges of motion and specific consequences is beyond the scope of this article, much information can be gleaned from simple comparisons right to left.

When evaluating the pelvis for alteration as a result of lower extremity postural change, it is helpful to consider the other causes of pelvic dysfunction that may be present. In addition to spinal changes, muscular dysfunction can cause pelvic gait errors. In the sagittal plane anterior pelvic tilt can be a result of weak hip extensors or hip flexion contracture. In the coronal plane contralateral hip abductor weakness, a short ipsilateral limb, or calf muscle weakness are just some of the causes of pelvic drop7

Therefore, something as simple as the assumed and documented pelvic anterior tilt as a result of pronation (asymmetric or bilateral) might not be so simple at all. The position of the pelvis is affected by factors such as acetabular orientation, soft tissue flexibility, muscular imbalances, and limb length, and all must be considered together when evaluating pelvic findings.

Reference List

(1) Pinto RZ. Man Ther 2008 December;13(6):513-9.

(2) Khamis S. Gait Posture 2007 January;25(1):127-34.

(3) McPoil TG. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 1996 November;24(5):309-14.

(4) Lun V. Br J Sports Med 2004 October;38(5):576-80.

(5) Franettovich M. J Foot Ankle Res 2010;3:5.

(6) Geraci MC. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am 2005 August;16(3):711-47.

(7) Perry J. Gait Analysis: Normal and Pathologic Function. Thorofare: SLACK Inc.; 1992.

CBP Seminars | Comments Off |

CBP Seminars | Comments Off |